A radio telescope located in outback Western Australia has observed a cosmic phenomenon with a striking resemblance to a jellyfish.

Published today in The Astrophysical Journal, an Australian-Italian team used the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) telescope to observe a cluster of galaxies known as Abell 2877.

Lead author and PhD candidate Torrance Hodgson, from the Curtin University node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) in Perth, said the team observed the cluster for 12 hours at five radio frequencies between 87.5 and 215.5 megahertz.

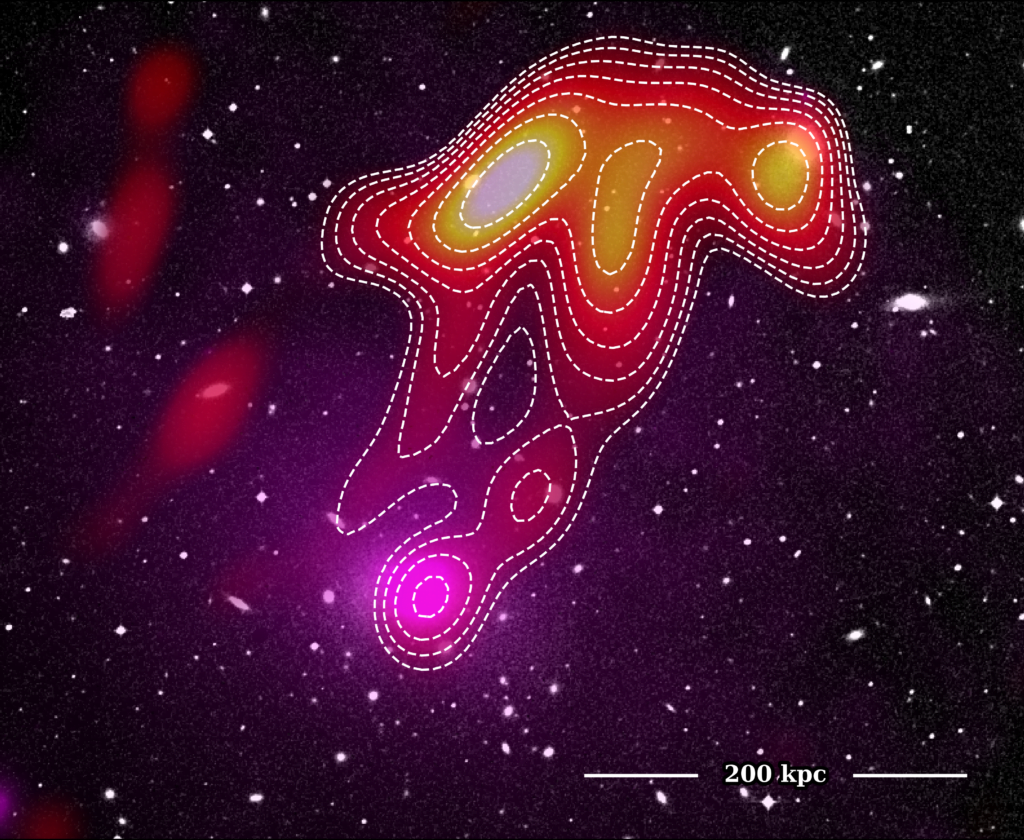

“We looked at the data, and as we turned down the frequency, we saw a ghostly jellyfish-like structure begin to emerge,” he said.

A composite image of the USS Jellyfish in Abell 2877 showing the optical Digitised Sky Survey (background) with XMM X-ray data (magenta overlay) and MWA 118 MHz radio data (red-yellow overlay). Credit: Torrance Hodgson, ICRAR/Curtin University.

“This radio jellyfish holds a world record of sorts. Whilst it’s bright at regular FM radio frequencies, at 200 MHz the emission all but disappears.

“No other extragalactic emission like this has been observed to disappear anywhere near so rapidly.”

This uniquely steep spectrum has been challenging to explain. “We’ve had to undertake some cosmic archaeology to understand the ancient background story of the jellyfish,” said Hodgson.

“Our working theory is that around 2 billion years ago, a handful of supermassive black holes from multiple galaxies spewed out powerful jets of plasma. This plasma faded, went quiet, and lay dormant.

“Then quite recently, two things happened—the plasma started mixing at the same time as very gentle shock waves passed through the system.

“This has briefly reignited the plasma, lighting up the jellyfish and its tentacles for us to see.”

The jellyfish is over a third of the Moon’s diameter when observed from Earth, but can only be seen with low-frequency radio telescopes.

“Most radio telescopes can’t achieve observations this low due to their design or location,” said Hodgson.

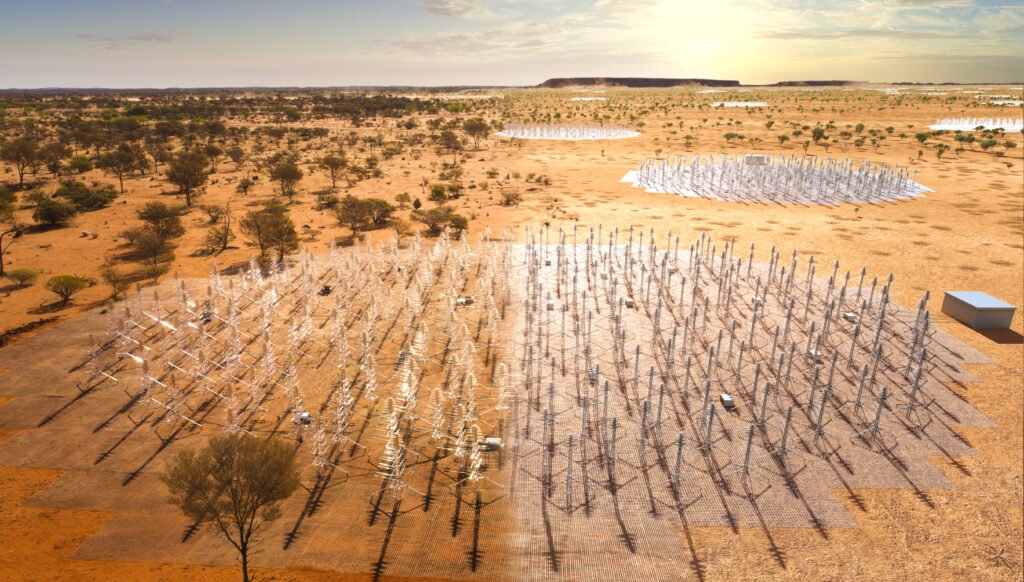

The MWA—a precursor to the Square Kilometre Array (SKA)—is located at CSIRO’s Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory in remote Western Australia.

The site has been chosen to host the low-frequency antennas for the SKA, with construction scheduled to begin in less than a year.

Tile 107, or “the Outlier” as it is known, is one of 256 tiles of the MWA located 1.5km from the core of the telescope. The MWA is a precursor instrument to the SKA. Photographed by Pete Wheeler, ICRAR.

Professor Johnston-Hollitt, Mr Hodgson’s supervisor and co-author, said the SKA will give us an unparalleled view of the low-frequency Universe.

“The SKA will be thousands of times more sensitive and have much better resolution than the MWA, so there may be many other mysterious radio jellyfish waiting to be discovered once it’s operational.

“We’re about to build an instrument to make a high resolution, fast frame-rate movie of the evolving radio Universe. It will show us from the first stars and galaxies through to the present day,” she said.

“Discoveries like the jellyfish only hint at what’s to come, it’s an exciting time for anyone seeking answers to fundamental questions about the cosmos.”

Composite image of the SKA-Low telescope in Western Australia. The image blends a real photo (on the left) of the SKA-Low prototype station AAVS2.0 which is already on site, with an artists impression of the future SKA-Low stations as they will look when constructed. These dipole antennas, which will number in their hundreds of thousands, will survey the radio sky in frequencies as low at 50Mhz. Credit ICRAR and SKAO.

Original Publication:

‘Ultra-Steep Spectrum Radio Jellyfish Uncovered in Abell 2877’, published in The Astrophysical Journal on March 18th, 2021.

More Info:

ICRAR

The International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) is a joint venture between Curtin University and The University of Western Australia with support and funding from the State Government of Western Australia.

Murchison Widefield Array

The Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) is a low-frequency radio telescope and is the first of four Square Kilometre Array (SKA) precursors to be completed. A consortium of partner institutions from seven countries (Australia, USA, India, New Zealand, Canada, Japan, and China) financed the development, construction, commissioning, and operations of the facility. The MWA consortium is led by Curtin University.

Contacts:

Professor Melanie Johnston-Hollitt (ICRAR / Curtin University)

Ph: +61 400 951 815 E: Melanie.Johnston-Hollitt@curtin.edu.au

Pete Wheeler (Media Contact, ICRAR)

Ph: +61 423 982 018 E: Pete.Wheeler@icrar.org

Vanessa Beasley (Media Contact, Curtin University)

Ph: +61 8 9266 1811 E: Vanessa.Beasley@curitn.edu.au