Australian researchers using a CSIRO radio telescope in Western Australia have nearly doubled the known number of ‘fast radio bursts’— powerful flashes of radio waves from deep space.

The team’s discoveries include the closest and brightest fast radio bursts ever detected.

Their findings were reported today in the journal Nature.

An artist’s impression showing one of CSIRO’s ASKAP radio telescope antennas observing a fast radio burst (FRB). Credit: OzGrav, Swinburne University of Technology.

Fast radio bursts come from all over the sky and last for just milliseconds.

Scientists don’t know what causes them but it must involve incredible energy—equivalent to the amount released by the Sun in 80 years.

“We’ve found 20 fast radio bursts in a year, almost doubling the number detected worldwide since they were discovered in 2007,” said lead author Dr Ryan Shannon, from Swinburne University of Technology and the OzGrav ARC Centre of Excellence.

“Using the new technology of the Australia Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP), we’ve also proved that fast radio bursts are coming from the other side of the Universe rather than from our own galactic neighbourhood.”

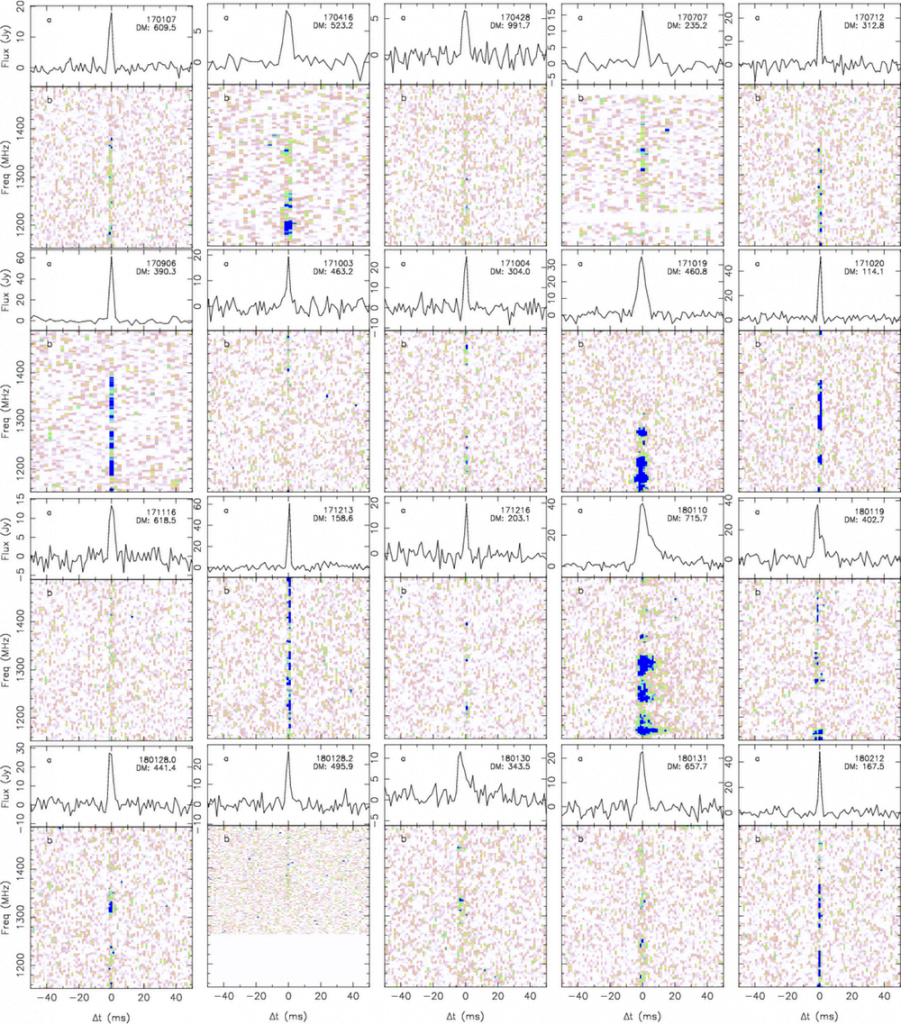

For each burst, the top panels show what the FRB signal looks like when averaged over all frequencies. The bottom panels show how the brightness of the burst changes with frequency. The bursts are vertical because they have been corrected for dispersion. Credit: Ryan Shannon and the CRAFT collaboration

Co-author Dr Jean-Pierre Macquart, from the Curtin University node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR), said bursts travel for billions of years and occasionally pass through clouds of gas.

“Each time this happens, the different wavelengths that make up a burst are slowed by different amounts,” he said.

“Eventually, the burst reaches Earth with its spread of wavelengths arriving at the telescope at slightly different times, like swimmers at a finish line.

“Timing the arrival of the different wavelengths tells us how much material the burst has travelled through on its journey.

“And because we’ve shown that fast radio bursts come from far away, we can use them to detect all the missing matter located in the space between galaxies—which is a really exciting discovery.”

An artist’s impression of CSIRO’s Australian SKA Pathfinder (ASKAP) radio telescope observing ‘fast radio bursts’ in ‘fly’s eye mode’. Each antenna points in a slightly different direction, giving maximum sky coverage. Credit: OzGrav, Swinburne University of Technology.

CSIRO’s Dr Keith Bannister, who engineered the systems that detected the bursts, said ASKAP’s phenomenal discovery rate is down to two things.

“The telescope has a whopping field of view of 30 square degrees, 100 times larger than the full Moon,” he said.

“And, by using the telescope’s dish antennas in a radical way, with each pointing at a different part of the sky, we observed 240 square degrees all at once—about a thousand times the area of the full Moon.

“ASKAP is astoundingly good for this work.”

Antennas of CSIRO’s Australian SKA Pathfinder with the Milky Way overhead. Credit: Alex Cherney/CSIRO

Dr Shannon said we now know that fast radio bursts originate from about halfway across the Universe but we still don’t know what causes them or which galaxies they come from.

The team’s next challenge is to pinpoint the locations of bursts on the sky.

“We’ll be able to localise the bursts to better than a thousandth of a degree,” Dr Shannon said.

“That’s about the width of a human hair seen ten metres away, and good enough to tie each burst to a particular galaxy.”

ASKAP is located at CSIRO’s Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory (MRO) in Western Australia, and is a precursor for the future Square Kilometre Array (SKA) telescope.

The SKA could observe large numbers of fast radio bursts, giving astronomers a way to study the early Universe in detail.

CSIRO acknowledges the Wajarri Yamaji as the traditional owners of the MRO site.

A fast radio burst leaves a distant galaxy, travelling to Earth over billions of years and occasionally passing through clouds of gas in its path. Each time a cloud of gas is encountered, the different wavelengths that make up a burst are slowed by different amounts. Timing the arrival of the different wavelengths at a radio telescope tells us how much material the burst has travelled through on its way to Earth and allows astronomers to to detect “missing” matter located in the space between galaxies. Credit: CSIRO/ICRAR/OzGrav/Swinburne University of Technology

Dr Ryan Shannon (Swinburne/OzGrav), Dr Jean-Pierre Macquart (Curtin/ICRAR) and Dr Keith Bannister (CSIRO) describe their discovery of 20 new fast radio bursts (FRBs) and how the Phased Array Feed (PAF) receiver technology in CSIRO’s Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) radio telescope enabled this breakthrough science. Credit: CSIRO. Video Transcript (RTF).

Original Publication:

‘The dispersion-brightness relation for fast radio bursts from a wide-field survey’, published in Nature on October 10th, 2018.

More Information:

ASKAP

The Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) is the world’s fastest survey radio telescope. Designed and engineered by CSIRO, ASKAP is made up of 36 ‘dish’ antennas, spread across a 6km diameter, that work together as a single instrument called an interferometer. The key feature of ASKAP is its wide field of view, generated by its unique phased array feed (PAF) receivers. Together with specialised digital systems, the PAFs create 36 separate (simultaneous) beams on the sky which are mosaicked together into a large single image.

Multimedia:

If you require imagery and video content for media purposes, please email pete.wheeler@icrar.org.

An artist’s impression of fast radio bursts in the sky above CSIRO’s ASKAP radio telescope at the Murchison radio-astronomy Observatory. Each antenna can observe 36 circular patches of sky and in the “fly’s eye” configuration each antenna can be pointed in a different direction, enabling ASKAP to detect the brightest and rarest fast radio bursts. Credit: OzGrav, Swinburne University of Technology.

An artist’s impression of fast radio bursts (FRBs). An Australian team of researchers has shown that the brighter FRBs, discovered using CSIRO’s ASKAP radio telescope, are probably in galaxies that are quite nearby, while fainter ones (found previously) are likely to be much more distant. Credit: OzGrav, Swinburne University of Technology.

An artist’s impression of CSIRO’s ASKAP radio telescope detecting a fast radio burst (FRB). Scientists don’t know what causes FRBs but it must involve incredible energy—equivalent to the amount released by the Sun in 80 years. Credit: OzGrav, Swinburne University of Technology.

An artist’s impression showing fast radio bursts in the sky above CSIRO’s ASKAP radio telescope. Fast radio bursts come from all over the sky and last for just milliseconds. ASKAP is located at the Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory— the future site in Australia for the Square Kilometre Array (SKA). Credit: OzGrav, Swinburne University of Technology.

Contacts:

Dr Ryan Shannon — Swinburne University of Technology & OzGrav ARC Centre of Excellence

Ph: +61 3 9214 5205 E: rshannon@swin.edu.au

Dr Jean-Pierre Macquart — ICRAR / Curtin University

Ph: +61 8 9266 9248 E: jean-pierre.macquart@icrar.org

Dr Keith Bannister — CSIRO

Ph: +61 2 9372 4295 E: keith.bannister@csiro.au

Pete Wheeler — Media Contact, ICRAR

Ph: +61 423 982 018 E: pete.wheeler@icrar.org